Motivation for this blog post:

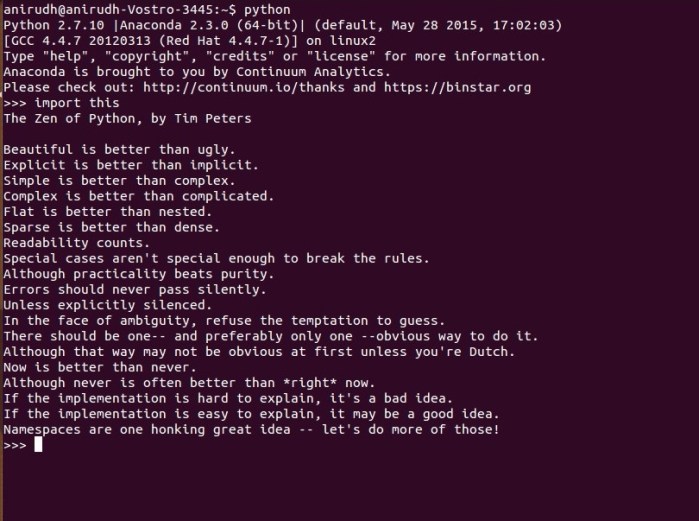

I had downloaded Canopy at the insistence of the instructors of MIT’s introductory course on computer science using Python. That said, I rarely ever used it. I’ve all along been working on Python using a text editor and command line only. I also downloaded Anaconda and started working on IPython since I began working on a new machine learning MOOC offered by the University of Washington via Coursera. Anaconda is awesome! It has all the best scientific libraries and I love IPython compared to PyCharm or Canopy, which pale in comparison to IPython, especially if you’re using Python for Machine Learning.

Anyway, I was working on IPython, trying to import matplotlib, when I got the following ImportError:

I noticed that the matplotlib library was trying to be accessed in Canopy’s Enthought directory. Since I never used or liked Canopy anyway, I decided to uninstall, bitch!

Step by step process of uninstalling Canopy from Linux:

1) From the Canopy preferences option in the Edit menu, mark off Canopy as your default Python (this step is not available on very early versions of Canopy).

2) Restart your computer.

3) Remove the “~/Canopy” directory (or the directory where you installed Canopy).

rm -rf Canopy

4) For each Canopy user, delete one or more of the directories below, which contain that user’s “System” and “User” virtual environments, and any user macros.

- Deleting “System” removes the environment where the Canopy GUI application runs; it will be re-created the next time that you start Canopy.

- Deleting “User” removes all your installed Python packages; it will be re-created with only the packages bundled into the Canopy installer, the next time that you start Canopy.

- Deleting the third directory will remove any Canopy macros which you may have written. It is usually empty. I did this from the desktop home directory itself.

(for 32-bit Canopy, replace “64bit” with “32bit”):

~/Enthought/Canopy_64bit/System

~/Enthought/Canopy_64bit/User

~/canopy

For a 64 bit system:

cd Enthought/Canopy_64bit

for a 32 bit system:

cd Enthought/Canopy_32bit

rm -rf System

rm -rf User

5) Delete the file “locations.cfg” from each user’s Canopy configuration / preferences directory. For complete Canopy removal, delete this directory entirely; if you do so, the user will lose individual preferences such as fonts, bookmarks, and recent file list.

cd ~/.canopy

cd ..

rm -rf .canopy

6) If you are uninstalling completely, edit the following files to delete any lines which reference Canopy (usually, the Canopy-related lines will have been commented out by step 1 but on some system configurations the lines might remain):

For this step, refer to my blog post on opening files in a text editor from the CMD / Terminal (Using Python).

~/.bashrc

~/.bash_profile

~/.profile

7) Restart your computer.

All these steps in one:

Once I was done with these steps, I no longer encountered any issues importing matplotlib on IPython anymore.

single-digit multiplications in general (and exactly

single-digit multiplications in general (and exactly  when n is a power of 2). Although the familiar grade school algorithm for multiplying numbers is how we work through multiplication in our day-to-day lives, it’s slower (

when n is a power of 2). Although the familiar grade school algorithm for multiplying numbers is how we work through multiplication in our day-to-day lives, it’s slower ( ) in comparison, but only on a computer, of course!

) in comparison, but only on a computer, of course!

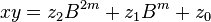

and

and  be represented as

be represented as  -digit strings in some

-digit strings in some  . For any positive integer

. For any positive integer  less than

less than

,

, and

and  are less than

are less than  . The product is then

. The product is then

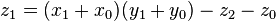

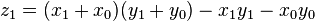

can be computed in only three multiplications, at the cost of a few extra additions. With

can be computed in only three multiplications, at the cost of a few extra additions. With  and

and  as before we can calculate

as before we can calculate

, where

, where  .

.