The most conventional approach to determine structural breaks in longitudinal data seems to be the Chow Test.

From Wikipedia,

The Chow test, proposed by econometrician Gregory Chow in 1960, is a test of whether the coefficients in two linear regressions on different data sets are equal. In econometrics, it is most commonly used in time series analysis to test for the presence of a structural break at a period which can be assumed to be known a priori (for instance, a major historical event such as a war). In program evaluation, the Chow test is often used to determine whether the independent variables have different impacts on different subgroups of the population.

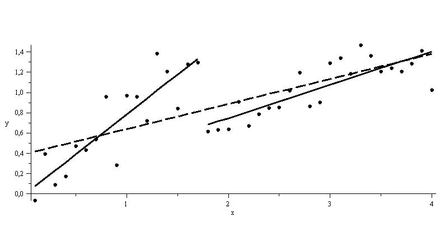

As shown in the figure below, regressions on the 2 sub-intervals seem to have greater explanatory power than a single regression over the data.

For the data above, determining the sub-intervals is an easy task. However, things may not look that simple in reality. Conducting a Chow test for structural breaks leaves the data scientist at the mercy of his subjective gaze in choosing a null hypothesis for a break point in the data.

Instead of choosing the breakpoints in an exogenous manner, what if the data itself could learn where these breakpoints lie? Such an endogenous technique is what Bai and Perron came up with in a seminal paper published in 1998 that could detect multiple structural breaks in longitudinal data. A later paper in 2003 dealt with the testing for breaks empirically, using a dynamic programming algorithm based on the Bellman principle.

I will discuss a quick implementation of this technique in R.

Brief Outline:

Assuming you have a ts object (I don’t know whether this works with zoo, but it should) in R, called ts. Then implement the following:

| # assuming you have a 'ts' object in R | |

| # 1. install package 'strucchange' | |

| # 2. Then write down this code: | |

| library(strucchange) | |

| # store the breakdates | |

| bp_ts <- breakpoints(ts ~ 1) | |

| # this will give you the break dates and their confidence intervals | |

| summary(bp_ts) | |

| # store the confidence intervals | |

| ci_ts <- confint(bp_ts) | |

| ## to plot the breakpoints with confidence intervals | |

| plot(ts) | |

| lines(bp_ts) | |

| lines(ci_ts) |

An illustration

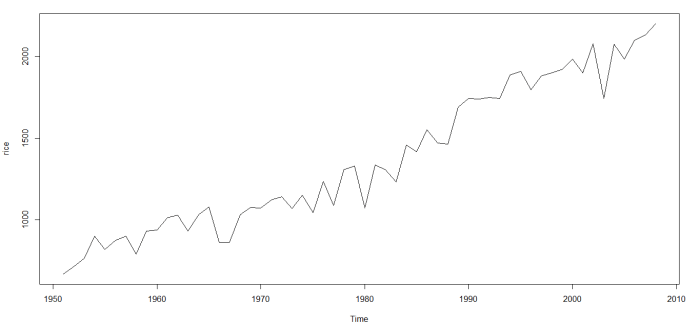

I started with data on India’s rice crop productivity between 1950 (around Independence from British Colonial rule) and 2008. Here’s how it looks:

You can download the excel and CSV files here and here respectively.

Here’s the way to go using R:

| library(xlsx) | |

| library(forecast) | |

| library(tseries) | |

| library(strucchange) | |

| ## load the data from a CSV or Excel file. This example is done with an Excel sheet. | |

| prod_df <- read.xlsx(file = 'agricultural_productivity.xls', sheetIndex = 'Sheet1', rowIndex = 8:65, colIndex = 2, header = FALSE) | |

| colnames(prod_df) <- c('Rice') | |

| ## store rice data as time series objects | |

| rice <- ts(prod_df$Rice, start=c(1951, 1), end=c(2008, 1), frequency=1) | |

| # store the breakpoints | |

| bp.rice <- breakpoints(rice ~ 1) | |

| summary(bp.rice) | |

| ## the BIC chooses 5 breakpoints; plot the graph with breakdates and their confidence intervals | |

| plot(bp.rice) | |

| plot(rice) | |

| lines(bp.rice) | |

| ## confidence intervals | |

| ci.rice <- confint(bp.rice) | |

| ci.rice | |

| lines(ci.rice) | |

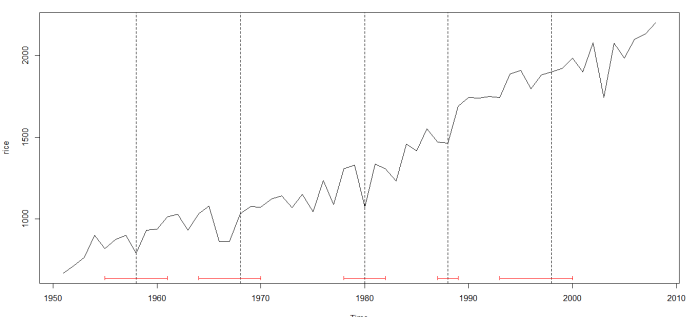

Voila, this is what you get:

The dotted vertical lines indicated the break dates; the horizontal red lines indicate their confidence intervals.

This is a quick and dirty implementation. For a more detailed take, check out the documentation on the R package called strucchange.